Where Is the Largest Budweiser Brewery in the United States

Philip Caputo traveled from Key West, Florida, to Deadhorse, Alaska, asking everyday Americans what holds our country together. In the end, it all came down to one beautiful word.

In Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman celebrates the races and nationalities of America, making "a thousand diverse contributions" to the nation's one identity, its "ever-united lands." Comparing Americans to the leaves on a many-branched tree, he invites the readers of his poem to gather for themselves "bouquets of the incomparable feuillage of These States."

Looking back on it, I think that's what I was doing when I recently made the longest road trip of my life: accepting Whitman's invitation, gathering bouquets.

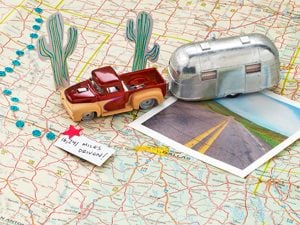

Towing a leased, antique Airstream trailer behind a pickup truck, I traveled with my wife, Leslie, and our two English setters, Sage and Sky, from the southernmost point in the continental United States, Key West, Florida, to the northernmost reachable by road, Deadhorse, Alaska, on the gray shores of the Arctic Ocean.

The four of us drove through 18 states and northwestern Canada, past more trees and under wider skies than we ever could have imagined. We baked in temperatures of over 100 degrees for weeks, witnessed the spectacular lightning and hailstorms of the Midwest, and, eventually, drove through a snowstorm.

The circuitous route back home in Connecticut took us down into Texas, where we handed the Airstream back to its owner. Altogether, we covered 16,241 miles in a little under four months.

Some friends and relatives said I was nuts to attempt such a monumental journey at my age—70. But I'd been inspired by the memory of the day, in 1996, when I was in Kaktovic, a settlement on windswept Barter Island, just off Alaska's north coast. I marveled that its Inupiat Eskimo schoolchildren pledged allegiance to the same flag as the children of Cuban immigrants in Key West, 6,000 miles away. Two islands farther apart than New York City is from Moscow and yet part of the same country.

It seemed almost miraculous that a nation so vast, peopled by nearly every race and ethnicity and religion on earth, managed to stay in one piece. What, I wondered, held the United States together?

Years after that Alaska trip, I was asking myself a variation of that question. Was the nation holding together as well as it once did? From reading and listening to the news, I had the impression that Whitman's "ever-united lands" had fragmented into a patchwork nation of red and blue states where no one could agree about much of anything.

But how accurate was that impression? As Leslie and I left Key West, I resolved to find out by asking everyday Americans the same question I'd put to myself: What holds us together?

I spoke with more than 80 people: white, Latino, African American, and Native American. They came from all walks of life, including a politician in Florida and another in Alaska, a farm woman in Missouri, a wrangler in Montana, college kids living on a commune in Tennessee, an ice-road trucker, and a taco entrepreneur who was also a Lakota Sioux shaman.

When Leslie and I arrived in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, that city and most of northern Alabama were still recovering from deadly tornadoes that had struck in a single day about a month earlier. Parts of Tuscaloosa looked as if they'd been carpet bombed.

We volunteered to help with the relief effort. A coordinator at the volunteer center told us that more than 14,000 people from almost every state in the union had pitched in. He asked us to write our initials on an acetate-covered map of the United States that showed the volunteers' home states. Did I want to discover the force that bound the atoms of America one to the other? Maybe I was looking at it: a spirit that had moved thousands of men and women to travel great distances to aid fellow citizens in distress.

We were assigned to a hangarlike warehouse, where we were buffeted by industrial fans that were all but useless in the 102-degree heat. We loaded boxes with food, medicine, and clothing alongside about 20 other volunteers, mostly young people from church groups. The volunteers were white; their supervisors, from the Seventh-Day Adventist disaster relief services, were black.

This in Tuscaloosa, where in 1963, Governor George Wallace vowed in his inauguration speech, "Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!"

Two weeks later, after sojourning in Mississippi and Tennessee, we were camped on Meramec Farm, in the green Missouri Ozarks. It's owned by Carol Springer, a compact blonde who raises cattle and horses on 470 acres. The farm has been in her family for seven generations.

As we sat in her kitchen sipping lemonade, she gave me her perspective on what puts the unum in our national motto, E pluribus unum: "The glue is a belief that's not clearly defined: that we have more in common than not, that we're more alike than we're different. I'm not sure it's true, but the important thing is that we believe it is."

"In other words," I asked, "the perception becomes the reality?"

Springer shrugged. "I've been known to believe I'll get home in the dark in the rain. I'm not convinced, but I believe I will, and I get there."

We moved on from Missouri, crossing the oceanic expanses of the Great Plains, to the South Dakota badlands. There, near the depressed Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, we stopped in a diner. "You should meet Ansel Woodenknife," the cook said after I ordered fry-bread tacos. "He's quite a guy."

The next day, I called on Woodenknife, who'd invented the fry-bread taco dish, at his house in Interior. A broad-faced, strongly built man greeted me at the front door. Busy with studying for an EMT test, he couldn't talk then but dropped by our campsite a couple of nights later.

Woodenknife, too, was amazed by the size and diversity of the United States, and that it didn't somehow fall to pieces.

"It's because of change," he told me. "This is the only country where everything changes all the time. People come here expecting change, and if they're going to survive, if they're going to be successful, they've got to learn to adapt to change, to different people from different races."

Woodenknife's formal education ended in the ninth grade, but he earned a doctorate in adaptation. Born on the neighboring Rosebud reservation, raised as one of 12 children in a cabin without electricity or running water, he was taken from his parents at age nine—against their wishes—and placed in a white foster home in Philadelphia. That happened to thousands of Native American children, caught up in a government program to "de-Indianize" them.

It didn't work in Woodenknife's case. He ran away so often that he was branded "incorrigible" and sent back to the reservation, where he learned to cling more fiercely to his traditional culture, eventually becoming a Lakota Sun-Dancer.

He also became an entrepreneur, running a busy restaurant and marketing Indian fry-bread tacos to supermarket chains across the country. In 2003, he was inducted into South Dakota's Small Business Hall of Fame.

Citing himself as an example, Woodenknife didn't think the melting pot was the way to national unity. Rather, he said, each American should try to stay true to his or her ethnic heritage while keeping an American identity. The fabric of the country would then be, he said, "a blanket of color, all sewn into the shape of the United States."

Leslie and I stayed off interstates for the most part, sticking to old routes like the Natchez Trace, blazed by early American settlers, and the Lewis and Clark Trail, a network of major highways and back roads following the route taken by the Lewis and Clark expedition in 1804 to 1806.

At a Montana dude ranch, we rode alpine meadows with a young wrangler, Annaliese Apel. Barely five feet tall, Apel described herself as a onetime "girl gangster" who'd grown up on the east side of St. Paul. She'd turned to wrangling horses to save herself from that life.

Apel embraced the dissension I feared was tearing at the nation's seams.

"I think the country definitely is in disarray," she said. "At the same time, to grow as a country, we need to have conflict, and conflict is healthy. But the media has this awesome way of blowing it out of proportion."

The Lewis and Clark Trail eventually brought us to the Pacific Coast. We headed north, crossed the Canadian border, and made our way up the storied Alaska Highway through British Columbia and the Yukon into Alaska.

There, north of Fairbanks, we picked up the northernmost road in the United States: the Dalton Highway, more than 400 miles of gravel and buckled asphalt. Road conditions make it a risky drive, and the scenery—endless stretches of mountains and tundra, the trans-Alaska oil pipeline crossing and recrossing the landscape—can be hypnotic. But we had only one mishap, a flat tire, before reaching our goal. Seventy-nine days after starting out from Key West, we stood on the shores of the Arctic Ocean.

We dipped our toes—briefly, because polar bears had been seen nearby—and I added Arctic water to a bottle I'd already filled partway with water from the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

Five thousand miles and three weeks later, I dropped the Airstream off in Breckenridge, Texas. There, I heard the most succinct answer to my Big Question. It was given by the Airstream's owner, Erica Sherwood, a 37-year-old small-business owner. As I sat telling traveler's tales to Erica and her husband, Jef, she turned the tables by throwing the question back at me.

Taking my cue from Annaliese Apel's remarks about conflict, I used a metaphor from astronomy: A star remains a star because of the "dynamic disequilibrium" between its gravity, which pulls it inward, and nuclear fusion, which sends its matter flying outward. If there is too much of one or the other, it either collapses in on itself or blows apart.

Almost from its birth, America has been pulled in the direction of maximum individual liberty by Thomas Jefferson's idea that the government that governs least governs best, and in the opposite direction by Alexander Hamilton's belief in centralized power. It is the perpetual but equal conflict between these extremes that generates the binding force, I said. Too much Jefferson could lead to anarchy, too much Hamilton to tyranny.

Erica and Jef found that a little weird and abstract, so I asked for Erica's thoughts on what united Americans, and she nailed it.

"It's hope," she said. "Isn't that what it's always been?"

Philip Caputo is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist and the author of 15 books. His newest is The Longest Road, from which this essay is adapted.

Where Is the Largest Budweiser Brewery in the United States

Source: https://www.rd.com/article/what-unites-these-states/

0 Response to "Where Is the Largest Budweiser Brewery in the United States"

Post a Comment